This is an edited version of an article previously published in the now defunct magazine Classical Recordings Quarterly.

A famous 1921 portrait by Jacques-Émile Blanche entitled ‘Le groupe des Six’ depicts five of the six composers known as Les Six with their ‘godfather’ Jean Cocteau (Louis Durey is missing, having seceded from the group, but the pianist-composer Jean Wiener is in the background). The focal point of the picture is an elegant young woman, the pianist Marcelle Meyer. Although not officially a member of the group, Meyer was muse to this groundbreaking group of composers and important figure in the Parisian musical scene in the early decades of the 20th century, although far less known than other pianists of her generation despite her phenomenal pianism and close relationship with important composers, musicians, and artists.

Marcelle Meyer was born on May 22, 1897 in Lille, France. Her elder sister Germaine, also a gifted pianist, gave the child her first lessons. When it became clear that Marcelle was worthy of a more formal musical education, her father allowed her to go to Paris in 1911 to study at the Conservatoire with Marguerite Long. It was not long before Meyer moved to the class of Alfred Cortot, whom she revered. His interpretative freedom, deep tone production and imaginative outlook clearly resonated with her, and years later she still called him ‘mon Maître’.

Meyer’s lessons with the Catalan pianist Ricardo Viñes had a major impact on her artistry. A contemporary and preferred interpreter of Debussy, Ravel, Albéniz and Falla, Viñes dedicated his life to promoting new music at the expense of his popularity (he died penniless). His clear, direct style and steadfast dedication to his musical peers strongly influenced Meyer’s devotion and unusually frank approach to modern music. She also studied with José Iturbi, who gave her further insights into the Spanish school.

A new era

Marriage in 1917 to the actor and producer Pierre Bertin whisked Marcelle into the burgeoning realm of the new artistic movement in Paris. Bertin introduced his attractive wife to the composer Eric Satie, who affectionately called her ‘Dadame.’ And on meeting Diaghilev, Meyer was immediately commissioned to perform in his upcoming production of Satie’s Parade. The premiere was a scandal yet Meyer revelled in the bold artistry of the production and took no notice of the near riot that ensued. Claude Debussy was at the performance, giving credence to the rumours that Meyer prepared his Préludes with him before his death nearly a year later.

Marriage in 1917 to the actor and producer Pierre Bertin whisked Marcelle into the burgeoning realm of the new artistic movement in Paris. Bertin introduced his attractive wife to the composer Eric Satie, who affectionately called her ‘Dadame.’ And on meeting Diaghilev, Meyer was immediately commissioned to perform in his upcoming production of Satie’s Parade. The premiere was a scandal yet Meyer revelled in the bold artistry of the production and took no notice of the near riot that ensued. Claude Debussy was at the performance, giving credence to the rumours that Meyer prepared his Préludes with him before his death nearly a year later.

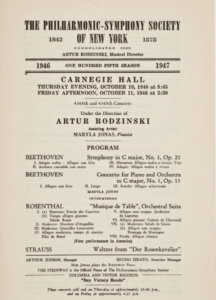

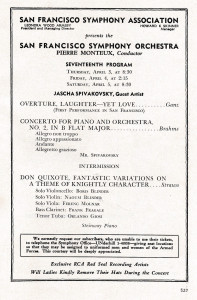

Meyer premiered several works of Les Six, including the Mouvements perpétuels by Poulenc, Chandelles romaines by Durey, and Printemps, Alfama, and Scaramouche by Milhaud. She introduced the two-piano version of Ravel’s La valse with the composer at the other keyboard, and while the private performance of April 16, 1920 did little for Ravel’s prospects of producing the ballet, Meyer appears to have won over Stravinsky: he asked her to perform Petrushka with Monteux in 1921 and was delighted with the results, and she was chosen as one of the four pianists to premiere Les noces.

Her career

Meyer crossed the Atlantic only once, travelling to South America in July-August 1927 to accompany the soprano Jane Bathori in Buenos Aires, and in general her activities appear to have been more muted than her talent warranted. It has been suggested that her insistence on performing obscure music of the 18th and 20th centuries limited her appeal to a wider audience. Nevertheless, she did perform more popular works of Mozart, Liszt, Chopin, and Schumann. She also balanced programmes featuring works for piano and orchestra by contemporary composers Stravinsky, Ravel, Honegger, Strauss, and Milhaud with more mainstream concertos by Mozart, Beethoven, and Liszt.

In 1930-31 Meyer went on an extensive tour organized by Cortot’s agents Kiesgen-Delaet that took her to such cities as Salzburg, Vienna, Prague, Bucharest, Budapest, Constantinople, Cairo, Alexandria, and Beirut – in Budapest she played the Burleske under Strauss’s baton – and while she may not have had streams of return engagements, artistically she seems to have been a hit: George Enescu wrote her a postcard praising her ‘unforgettable’ performance of Beethoven’s C Minor Concerto. Her activities in Europe generally consisted of handfuls of concerts locally and a few regular engagements – she played in Amsterdam almost every year.

In 1930-31 Meyer went on an extensive tour organized by Cortot’s agents Kiesgen-Delaet that took her to such cities as Salzburg, Vienna, Prague, Bucharest, Budapest, Constantinople, Cairo, Alexandria, and Beirut – in Budapest she played the Burleske under Strauss’s baton – and while she may not have had streams of return engagements, artistically she seems to have been a hit: George Enescu wrote her a postcard praising her ‘unforgettable’ performance of Beethoven’s C Minor Concerto. Her activities in Europe generally consisted of handfuls of concerts locally and a few regular engagements – she played in Amsterdam almost every year.

Having divorced Bertin in 1927, a few years after their daughter was born, in 1932 Meyer married the Italian lawyer Carlo di Vieto, with whom she would have a second daughter; they lived in Paris until settling in Rome in 1947. Italy provided another galaxy of composers whose works she would advocate – Casella, Rieti, Petrassi, Veretti, Dallapiccola – while she travelled to France to record for Les Discophiles Français.

As discussions were under way for a tour of North America with Dimitri Mitropoulos, with whom she had played in Athens back in 1930, Meyer went to Paris for what would be the last time. During that visit, on November 17, 1958, she suffered a heart attack while at the piano in her sister’s apartment and died in hospital that night, aged 61.

A rich legacy

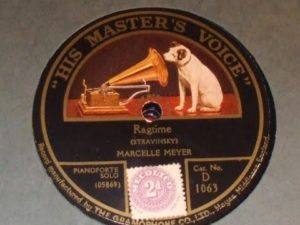

Meyer’s artistic testament is a vast discography spanning more than 20 hours of studio recordings and three decades. She signed a contract with HMV on June 15, 1925 and first recorded at Hayes on 30 June: Debussy’s Sérénade interrompue and Général Levine, eccentric (Matrix Bb 6272-1 & -2) and Chabrier’s Idylle (Matrix Bb6273-1, -2 & -3). Both sides were unpublished. On December 1st she returned to set down Poulenc’s Mouvements perpétuels (Matrix Bb7430-1, 2a & -3); Stravinsky’s Ragtime (HMV D1063, W727); Albéniz’s Navarra (D1063, W727) and Sous le palmier (E434, P725); Falla’s Dance of the Miller from The Three-Cornered Hat (E434, P725); a remake of Chabrier’s Idylle (Matrix Bb7437-1 & -2); and Debussy’s Poissons d’or (Bb7438-1 & -2). Takes of the Poulenc and Debussy were released in 1992 (EMI CZS7 67405-2) and the Chabrier was finally released on EMI France’s 17-disc tribute to the pianist in 2007. Although her contract was renewed for a year in 1926, nothing eventuated. She made two discs for French Columbia in 1929: Ravel’s Alborada del gracioso (LF11) and Chabrier’s Bourrée Fantasque (LF24).

Meyer’s artistic testament is a vast discography spanning more than 20 hours of studio recordings and three decades. She signed a contract with HMV on June 15, 1925 and first recorded at Hayes on 30 June: Debussy’s Sérénade interrompue and Général Levine, eccentric (Matrix Bb 6272-1 & -2) and Chabrier’s Idylle (Matrix Bb6273-1, -2 & -3). Both sides were unpublished. On December 1st she returned to set down Poulenc’s Mouvements perpétuels (Matrix Bb7430-1, 2a & -3); Stravinsky’s Ragtime (HMV D1063, W727); Albéniz’s Navarra (D1063, W727) and Sous le palmier (E434, P725); Falla’s Dance of the Miller from The Three-Cornered Hat (E434, P725); a remake of Chabrier’s Idylle (Matrix Bb7437-1 & -2); and Debussy’s Poissons d’or (Bb7438-1 & -2). Takes of the Poulenc and Debussy were released in 1992 (EMI CZS7 67405-2) and the Chabrier was finally released on EMI France’s 17-disc tribute to the pianist in 2007. Although her contract was renewed for a year in 1926, nothing eventuated. She made two discs for French Columbia in 1929: Ravel’s Alborada del gracioso (LF11) and Chabrier’s Bourrée Fantasque (LF24).

In 1938 Meyer went back to HMV for the famous recording of Milhaud’s newly composed Scaramouche (DB5086), with the composer at the other piano. Then followed her vivacious 1943 account of Strauss’s Burleske under André Cluytens’s baton (HMV W1565/6). Sadly a planned Ravel G Major Concerto was axed, as it was not thought commercial enough (how times have changed – the Ravel is far more popular today) – a most regrettable decision, as an unpublished live account from the 1930s shows that Meyer was in her element in this work.

In 1946 Meyer began to set down an array of older and newer music for Les Discophiles Français, for which she would be posthumously recognized with a Grand Prix du Disque in 1959. Founded in 1941 by Henri Screpel, an art book publisher, the Discophiles label set out to produce recordings by worthwhile artists lacking international renown: among their stable of pianists were Lili Kraus and Yves Nat. Marcelle Meyer focused on then rarely played repertoire such as Rameau, Scarlatti, Chabrier, and Stravinsky. Most of the sessions took place at Salle Adyar, on Avenue Rapp on the left bank. The piano used was a Hamburg Steinway chosen by Kraus, a surprising fact given its bell-like sonority and light action. Although Meyer tended to favour Pleyel pianos, she liked this Steinway and its rich tone and lightness of touch served her well, lending her performances great clarity and suppleness.

Under Screpel’s artistic direction, the Discophiles recordings were engineered by André Charlin, legendary for his wonderful tonal balance. Regrettably the surfaces of some of the 78rpm discs leave a great deal to be desired, and with Charlin’s focus on sound over other details, speeds can be erratic – many of the Bach discs were off pitch when released on CD in the 1990s because the masters were not recorded strictly at 78rpm. Recording dates are equally unreliable: sometimes what is documented is the day a transfer was made or a tape edited.

Under Screpel’s artistic direction, the Discophiles recordings were engineered by André Charlin, legendary for his wonderful tonal balance. Regrettably the surfaces of some of the 78rpm discs leave a great deal to be desired, and with Charlin’s focus on sound over other details, speeds can be erratic – many of the Bach discs were off pitch when released on CD in the 1990s because the masters were not recorded strictly at 78rpm. Recording dates are equally unreliable: sometimes what is documented is the day a transfer was made or a tape edited.

Given careful pitching, Meyer’s beautifully recorded Discophiles performances exhibit magnificent warmth and are musically beyond reproach. Presented in attractive textured gatefold cases, the records are sought after by collectors, many of whom will pay hundreds of dollars for original pressings. Some of the recordings were additionally released in the US on Haydn Society LPs: the Mozart concertos (HSL88), Stravinsky piano music (HSL113), and Ravel piano music (HSL111/2).

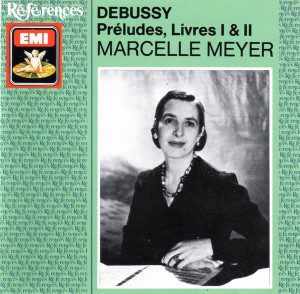

When Discophiles Français went bankrupt in 1958, Screpel disappeared, much to the chagrin of Meyer and her family, with whom he had developed a close friendship. The rights were purchased by Ducretet-Thomson and later passed to EMI. In the 1980s Rémi Jacobs, creator of the EMI Références series, brought Marcelle Meyer back into the catalogue after a decades-long absence with four two-LP sets of Rameau, Scarlatti, Chabrier and Ravel. In 1989 a Références CD of a previously unpublished recording of the complete Debussy Préludes was released (EMI CDH7 63348-2) as a bonus (if you bought three Références discs, you got the Meyer for free); the source for this recording a test record from her elder daughter’s collection for an LP that went unissued due to the dissolution of Les Discophiles Français.

When Discophiles Français went bankrupt in 1958, Screpel disappeared, much to the chagrin of Meyer and her family, with whom he had developed a close friendship. The rights were purchased by Ducretet-Thomson and later passed to EMI. In the 1980s Rémi Jacobs, creator of the EMI Références series, brought Marcelle Meyer back into the catalogue after a decades-long absence with four two-LP sets of Rameau, Scarlatti, Chabrier and Ravel. In 1989 a Références CD of a previously unpublished recording of the complete Debussy Préludes was released (EMI CDH7 63348-2) as a bonus (if you bought three Références discs, you got the Meyer for free); the source for this recording a test record from her elder daughter’s collection for an LP that went unissued due to the dissolution of Les Discophiles Français.

In 1992, EMI France released the first of three sets dedicated to Meyer in their Introuvables series, a six-CD box of 19th- and 20th-century music (CZS6 76405 2). With the release of the four-disc Vol.2 (CZS5 68092-2) and five-disc Vol.3 (CZS5 68498-2), Meyer’s near-complete commercial recordings had been issued by the mid-1990s. The only items not included were Espla’s Sonata del Sur, which in 2003 was released on an EMI Spain CD (5 62585-2), and some 78rpm versions of music she later recorded on tape. The 27 Scarlatti Sonatas from 1947 were issued separately with Bach’s C minor Toccata, BWV911 (Pearl GEM0137).

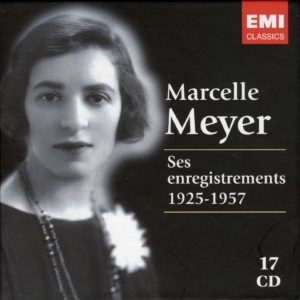

Rémi Jacobs’s last task before retiring from EMI France in 2007 was to produce a 17-CD set devoted to the complete commercial records of Marcelle Meyer (384699-2). It includes new transfers of every studio version of each work Meyer recorded, as well as a newly discovered Pleyela piano roll of Haydn’s Sonata in E Minor, Hob. XVI:34. Also being published for the first time since their initial release are works by Debussy recorded in 1947 (DF92/95), the Bourrée fantasque from 1929 and the studio version of the Mozart Sonata K310 (Album 37) – the previous EMI set had a broadcast transcription instead of the commercial recording.

Rémi Jacobs’s last task before retiring from EMI France in 2007 was to produce a 17-CD set devoted to the complete commercial records of Marcelle Meyer (384699-2). It includes new transfers of every studio version of each work Meyer recorded, as well as a newly discovered Pleyela piano roll of Haydn’s Sonata in E Minor, Hob. XVI:34. Also being published for the first time since their initial release are works by Debussy recorded in 1947 (DF92/95), the Bourrée fantasque from 1929 and the studio version of the Mozart Sonata K310 (Album 37) – the previous EMI set had a broadcast transcription instead of the commercial recording.

There are curious gaps in Meyer’s commercial discography. She did not record a note of Eric Satie, a peculiar omission given that she was his preferred pianist and she made only the one 78rpm side of Poulenc, odd given her close friendship with the composer. Romantic repertoire is largely absent – in the studio she set down works by Chabrier but no Chopin or Schumann, both of whose works she played frequently. A Dutch critic found her Études symphoniques to be ‘clear, healthy, purely musical, full of expression and character, without any … exaggerated romanticism’. It seems strange that Meyer should have opted to record two Mozart concertos but no other works for piano and orchestra during her tenure with Discophiles Français. Concerted works by Ravel, Franck or Saint-Saëns would have suited both her playing and the label’s focus on French repertoire.

The performances

The pianism of Marcelle Meyer is particularly striking in its simplicity. Her playing is graceful and supple, with melodic lines always clear and flexible. Her timing is impeccable, with each phrase meticulously measured for cadence and tone production: melodies rise and fall with fluidity and every note blends seamlessly into the next. Whether in Baroque keyboard music of Rameau and Couperin or in works by her contemporaries Debussy and Ravel, Meyer’s carefully controlled craftsmanship exhibits precise pedalling, a line that never loses focus, and a beautiful ringing piano sound.

Among her triumphs are the recordings of early keyboard music, in which she breathes new life into music that had gone largely unnoticed by pianists of her generation. To Bach, Scarlatti, Rameau, and Couperin she brings warmth and transparency with her clear tone, delicate phrasing, and deft fingerwork. Particularly remarkable is her ornamentation: her trills are not mere technical devices but a subtle shift of the melodic progression that produces a warbling effect without distorting the inflection or lilt of the line.

At a time when pianists might have played an occasional Scarlatti sonata or a Godowsky transcription of Rameau, Meyer set about recording extensive tributes to these composers. After making a few Rameau discs in 1946 (DF64/7), she taped his complete works in 1953, the first cycle on record (DF98/9). Her crystalline sound and clear phrasing assist her in capturing both the melancholic and exuberant moods prevalent in Rameau’s oeuvre. Particularly noteworthy is how she fluidly incorporates ornamentation into the melodic line, whereby trills are not merely decorative devices but an integral aspect of the melodic line.

The slower pieces feature beautifully terraced harmonies and the livelier ones are played with dynamism, as are nine Couperin works (72/9). Meyer recorded two batches of Scarlatti Sonatas, 27 of them in 1946 and 1948 (D68/71, 130/3) and 32 in 1954 (139/40). She launches into the sonatas with both verve and sensitivity, her flawless technique allowing her to bypass technical challenges and her sensitive ear enabling her to reveal depth inherent in pieces at the time often dismissed as superficial.

Among Meyer’s other ‘firsts’ were several Bach titles: the English Suite no.4 (Album 38), Partita no.3 (82/3), and Toccatas in D minor BWV913 (60/1) and F sharp minor BWV910 (Album 38) were the first piano performances of these works on record. In general Meyer approaches Bach’s works with a more robust attack and greater rhythmic vitality than with Rameau and Scarlatti, although in the Inventions and Sinfonias she phrases with a smooth sensuality that still clarifies the contrapuntal structure of these seldom-recorded works.

Meyer’s transparent textures and declamatory delivery serve Mozart’s idiom well. Although the Concertos K466 and K488 (37) are somewhat marred by the scraping strings of Maurice Hewitt’s orchestra, her playing is magnificent here and in several solo works. A few broadcasts of solo works (Tahra TAH579/80) have added to her official Mozart discography, but a forthright broadcast of the ‘Emperor’ Concerto is all that has been released of her Beethoven. Judging by the Haydn sonata roll, she had affection for his music. In five pieces from Rossini’s Péchés de ma vieillesse (EX25008), Meyer expresses the operatic nature of the writing with a strong lyrical line and sense of drama. She recorded a number of Schubert dances in 1948–49: Valses nobles, Ländler, Valses sentimentales and Danses allemandes (134/8), all despatched with vigour and enthusiasm.

Meyer’s Chabrier cycle (151/2) is one of the glories of recorded pianism, showing her to have been a romanticist of the highest order. She traverses his Pieces pittoresques with remarkable sensitivity, impeccable timing, and luscious piano tone, expressing the unique flavour of each work to perfection, without an ounce of self-indulgence or exaggeration. Idylle, which Meyer’s daughter calls ‘the soundtrack of (her) childhood’, has a seamlessly fluid melodic line over a baseline that is at times magnificently elastic, at others deliciously hazy yet never unclear. In Habañera, Meyer builds to a magnificent climax without sacrificing the sensual mood, and in Feuillet d’album, cascading figurations caress a hauntingly beautiful melody that is expressed with tenderness and fluidity.

Meyer apparently wished to record both piano parts of the Valses romantiques, hoping that they could be edited into a single performance. As the technology of the time made such double-tracking difficult, she invited her dear friend Francis Poulenc to the second piano, and the recording is a powerful testament to their musical sympathy.

Unlike a great many pianists, Meyer makes a palpable distinction between Debussy’s and Ravel’s idioms, impressionistic but not blurred in the former, attentive to structure and clarity in the latter. The Debussy Préludes are priceless documents, with amazingly subtle pedaling fused with full-bodied tone and remarkable feats of virtuosity; the 1947 ‘La terrace des audiences du claire de lune’ is utterly mesmerizing for its evocative colours, sumptuous phrasing, and magnificent timing. She also delivers superlative readings of L’isle joyeuse, Images, and Masques.

That Meyer’s Ravel cycle (100/1) won the 1955 Grand Prix du Disque is hardly surprising: her crystalline tone and precision are ideally suited to Ravel’s jewel-like oeuvre, and her relationships with the composer and his colleague Ricardo Viñes bring credibility to her approach. She pedals with moderation and applies the gentlest of rubatos, and her tempos are fairly brisk: her Pavane pour une infante défunte is, as Ravel suggested, not a dead pavane for a princess. Jeux d’eau sparkles like diamonds in sunlight (how marvellous her Jeux d’eau a la Villa d’Este of Liszt must have been – she played it in recital) and Le tombeau de Couperin highlights the biting harmonies with clear textures and rhythmic certainty. Her Gaspard de la nuit features a hypnotic Ondine, a haunting Le gibet, and a breathtaking Scarbo.

A prime exponent of the newest music of her generation, Meyer performs her contemporaries’ works with exuberance. The shorter works of Poulenc, Albéniz, and Falla recorded in 1925 are played with aplomb, the 1938 Scaramouche finds Meyer and Milhaud throwing caution to the wind, and 1943’s Strauss Burleske bubbles with excitement blended with lyrical poise. In the works of Stravinsky, Meyer’s clear textures allow for a transparent presentation of the complex harmonies and structures. Producer Antoine Duhamel reported that the only time he witnessed Meyer technically taxed was while recording the incredibly demanding Trois mouvements de Petrouchka (48, 163), yet the 55-year-old Meyer’s performance is stupendous, played with a more relaxed articulation than usual so as to highlight the jazzier side of the music than one usually hears. Her 1956 recording (Hispavox HH1001) of Espla’s Sonata del Sur, conducted by the composer, features stunning technical feats and a blend of lushly Romantic melodic expression and modern tonal construction.

One of the true highlights of the art of Marcelle Meyer is a broadcast of Nights in the Gardens of Spain (TAH564), recorded only six months before her death. The playing smoulders with a flexible rhythmic approach and richly textured figurations that bring to mind the sensual moves of Spanish dancers and the vibrato of a Flamenco guitar. How unfortunate that the Burleske she performed at the same concert has not been released.

It is remarkable to consider that a pianist present at the birth of the music of Satie, Debussy, Ravel, and Stravinsky should have left us over 20 hours of superlative recordings. Given the admiration of present-day pianists like Alexandre Tharaud, the fact that the Newport Music Festival has held two concerts in her memory, and the comprehensive re-release of her studio recordings, Marcelle Meyer may continue to influence future generations of music-lovers.

(c) Mark Ainley 2017

Recent Comments