Below is a list of known recordings of Dinu Lipatti. This discography is currently in draft format and will be revised.

June 25, 1936

Ecole Normale de Musique, Paris

1. Bach: Partita No.1 in B-Flat Major, BWV 825: Prelude, Sarabande, Allemande*

2. Bach-Lipatti: Improvisation (on Bach-Busoni Toccata in C)*

3. Brahms: Intermezzo in B-Flat Minor, Op.117 No.2 (abbr.)

4. Enescu: Sonata in F-Sharp, Op.24 No.1: ii. Presto vivace

5. Brahms: Intermezzo in E-Flat minor, Op.118 No.6

*Bach works performed on harpsichord

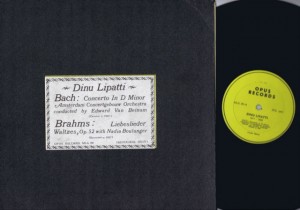

February 20, 1937; March 12, 1937; January 22, 1938

Salle Gouin, Paris

6. Brahms: Liebeslieder Walzer Op.52

with Nadia Boulanger, piano, Irene Kedroff (soprano), Marie-Blanche de Polignac (alto), Hugues Cuenod (tenor), Paul Derenne (tenor), Doda Conrad (bass)

February 25, 1937

Paris

7. Brahms: Waltzes for Piano 4-hands, Op.39: Nos. 6, 15, 2, 1, 14, 10, 5, 6

with Nadia Boulanger, piano

ca.1940-1941

Bucharest

8. Mozart-Busoni: Duettino Concertante for 2 pianos

with Madelaine Lipatti, piano

This unpublished test recording unfortunately deteriorated to the point that it could not be salvaged

April 28, 1941

Bucharest Broadcasting Studio, Bucharest

9. Bach-Hess: Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring (abbr)

10. Brahms: Intermezzo in A Minor, Op.116 No.2

11. Brahms: Intermezzo in E-Flat Major, Op.117 No.1

12. Chopin: Waltz No.2 in A-Flat Major, Op.34 No.1

13: Chopin: Etude in G-Flat Major, Op.10 No.5

14: Liszt: Concert Etude No.2: Gnomenreigen

15: Scarlatti: Sonata in G, L387 (Kk14)

16: Schumann: Etudes Symphoniques Op.13: No.9

Note: Some of these recordings may not have been recorded at this session. They were found in a private collection and Lipatti’s biographers Dragos Tanasescu and Grigore Bargauanu believed them all to be made on this, but this has not been verified.

January 14, 1943

Berlin

17. Lipatti: Concertino in Classical Style, Op.3

Hans von Benda, Berlin Chamber Orchestra

March 2, 1943

Romanian Broadcasting Studio, Bucharest

18. Enescu: Suite for Piano No.2 in D, Op.10: Bourree

March 4, 1943

Romanian Broadcasting Studio, Bucharest

19. Lipatti: Sonatina for left hand

March 11, 1943

Romanian Broadcasting Studio, Bucharest

20. Enescu: Violin Sonata No.3 in A Minor, Op.25

with Georges Enescu, violin

March 13, 1943

Romanian Broadcasting Studio, Bucharest

21. Enescu: Violin Sonata No.2 in F Minor, Op.6

with Georges Enescu, violin

October 18, 1943

Radio Bern

22. Enescu: Piano Sonata No.3 in D Major, Op.24

February 20, 1947

EMI Abbey Road Studio No.3, London

23. Scarlatti: Sonata in D Minor, L413 (Kk9)

24. Chopin: Nocturne No.8 in D-Flat Major, Op.27 No.2

March 1 and 4, 1947

EMI Abbey Road Studio No.3, London

25. Chopin: Piano Sonata No.3 in B Minor, Op.58

May 24, 1947

Wolfbach Studio, Zurich

26. Beethoven: Cello Sonata No.3 in A Major, Op.69: I. Allegro ma non tanto

27. Bach: Cello Sonata in D: II. Andante

28. Chopin: Nocturne in C-Sharp Minor

29. Faure: Apres un reve

30. Rimsky-Korsakov: The flight of the bumblebee

31. Ravel: Piece en forme de habanera

with Antonio Janigro, cello

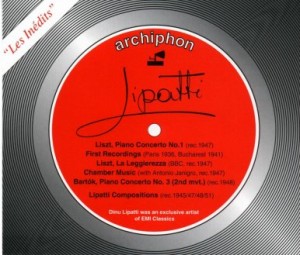

June 6, 1947

Grand Theatre, Geneva

32. Liszt: Piano Concerto No.1 in E-Flat Major

with Ernest Ansermet, Orchestre de la Suisse Romande

Note – At the same concert, Lipatti performed Chopin’s Andante Spianato and Polonaise, but that recording has not been found

September 18 and 19, 1947

EMI Abbey Road Studio No.1, London

33. Grieg: Piano Concerto in A Minor, Op.16

with Alceo Galliera, The Philharmonia Orchestra

September 24, 1947

EMI Abbey Road Studio No.3, London

34. Chopin: Waltz No.2 in A-Flat Major, Op.34 No.1

35. Bach-Hess: Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring

36. Liszt: Sonetto del Petrarca No.104

September 25, 1947

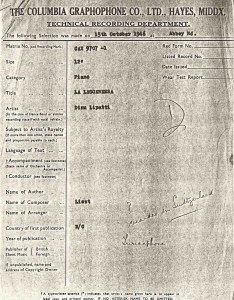

BBC Studios, London

37. Liszt: La Leggierezza

September 27, 1947

EMI Abbey Road Studio No.3, London

38. Scarlatti: Sonata in E Major, L.23 (Kk380)

October 2, 1947

Concertgebouw, Amsterdam

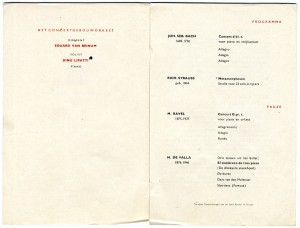

39. Bach-Busoni: Piano Concerto No.1 in D Minor, BWV 1052

with Eduard van Beinum, Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra

April 9 and 10, 1948

EMI Abbey Road Studio No.1, London

40. Schumann: Piano Concerto in A Minor, Op.54

with Herbert von Karajan, The Philharmonia Orchestra

April 17, 1948

EMI Abbey Road Studio No.3, London

41. Ravel: Alborada del Gracioso

April 17 and 21, 1948

EMI Abbey Road Studio No.3, London

42. Chopin: Barcarolle in F-Sharp Major, Op.60

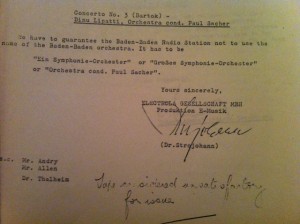

May 30, 1948

Studio Kurhaus, Grosser Buehnensaal, Baden-Baden

43. Bartok: Piano Concerto No.3

with Paul Sacher, Sinfonie-Orchester des Suedwestfunks

February 7, 1950

Tonhalle, Zurich

44. Chopin: Piano Concerto No.1 in E Minor, Op.11

with Otto Ackermann, Zurich Tonhalle-Orchester

45. Chopin: Nocturne No.8 in D-Flat Major, Op.27 No.2

46. Chopin: Etude No.17 in E Minor, Op.25 No.5

47. Chopin: Etude No.5 in G-Flat Major, Op.10 No.5

February 22, 1950

Victoria Hall, Geneva

48. Schumann: Piano Concerto in A Minor, Op.54

with Ernest Ansermet, Orchestre de la Suisse Romande

July 3-12, 1950

Studio 2, Radio Geneve

Chopin: Fourteen Waltzes

49. No.4 in F Major, Op.34 No.3 (July 9)

50. No.5 in A-Flat Major, Op.42 (July 11)

51. No.6 in D-Flat Major, Op.64 No.1 (July 6)

52. No.9 in A-Flat Major, Op.69 No.1 (July 3)

53. No.7 in C-Sharp Minor, Op.64 No.2 (July 3)

54. No.11 in G-Flat Major, Op.70 No.1 (July 3)

55. No.10 in B Minor, Op.69 No.2 (July 4)

56. No.14 in E Minor, Op. posth (July 12)

57. No.3 in A Minor, Op.34 No.2 (July 4)

58. No.8 in A-Flat Major, Op.64 No.3 (July 6)

59. No.12 in F Minor, Op.70 No.2 (July 5 and 9)

60. No.13 in D-Flat Major, Op.70 No.3 (July 9)

61. No.1 in E-Flat Major, Op.18 (July 9)

62. No.2 in A-Flat Major, Op.34 No.1 (July 8 )

July 6, 1950

Studio 2, Radio Geneve

63. Bach-Kempff: Siciliano

July 9, 1950

Studio 2, Radio Geneve

64. Bach: Partita No.1 in B-Flat Major, BWV 825

65. Mozart: Piano Sonata No.8 in A Minor, K 310

July 10, 1950

Studio 2, Radio Geneve

66. Bach-Busoni: Chorale Prelude, “Nun komm’, der Heiden Heiland”

67: Bach-Busoni: Chorale Prelude, “Ich ruf’ zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ”

68. Bach-Hess: Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring

July 11, 1950

Studio 2, Radio Geneve

69. Chopin: Mazurka No.32 in C-Sharp Minor, Op.50 No.3

July 27, 1950

Radio Geneve, Geneva

70. Interview with Francois Magnenat

71. Chopin: Waltz No.3 in A Minor, Op.34 No.2

72. Bach-Hess: Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring (excerpt)

73. Bach-Busoni: “Ich ruf’ zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ”

August 23, 1950

Kunsthaus, Lucerne

74. Interview with Henri Jaton

75. Mozart: Piano Concerto No.21 in C Major, K.467

with Herbert von Karajan, Orchester der Festspiele Luzern

September 16, 1950

Salle du Parlement, Besancon

76. Bach: Partita No.1 in B-Flat Major, BWV 825

77. Mozart: Piano Sonata No.8 in A Minor, K 310

78. Schubert: Impromptu No.3 in G-Flat Major, D.899 No.3

79. Schubert: Impromptu No.2 in E-Flat Major, D.899 No.2

Chopin: 13 Waltzes

80. No.5 in A-Flat Major, Op.42

81. No.6 in D-Flat Major, Op.64 No.1

82. No.9 in A-Flat Major, Op.69 No.1

83. No.7 in C-Sharp Minor, Op.64 No.2

84. No.11 in G-Flat Major, Op.70 No.1

85. No.10 in B Minor, Op.69 No.2

86. No.14 in E Minor, Op.posth

87. No.3 in A Minor, Op.34 No.2

88. No.4 in F Major, Op.34 No.3

89. No.12 in F Minor, Op.70 No.2

90. No.13 in D-Flat Major, Op.70 No.3

91. No.8 in A-Flat Major, Op.64 No.3

92. No.1 in E-Flat Major, Op.18

September 29, 1950

Radio Geneve, Geneva

93. Interview with Franz Walter

Note: The performance that Lipatti gave after the interview of the Bach-Kempff ‘Siciliano’ has not been located

Recent Comments