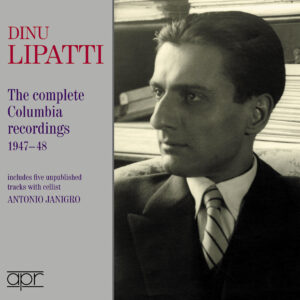

A new CD set has come out that is the culmination of an early discovery at the beginning of my research into unknown recordings of the pianist Dinu Lipatti – a production I am thrilled to have helped with and to which I contributed extensive booklet notes.

The first letter I received from EMI’s London office in 1989 mentioned a set of unpublished recordings that the legendary pianist had made with the cellist Antonio Janigro, stating that they had been in the collection of Elisabeth Schwarzkopf – widow of Lipatti’s recording producer Walter Legge – but they had been taken and not returned. Nobody in the well-informed piano recording underground had heard about the existence of these performances and I was naturally intrigued – especially as one of the works they recorded was the first movement of Beethoven’s Third Cello Sonata.

I had not yet discovered the extent to which it was a myth that Lipatti did not play Beethoven until the last two years of his life – this was a complete fabrication by Legge, 100% untrue, easily provable now with the material that I have gathered. Since no other recordings of Lipatti playing Beethoven have surfaced – yet – this one with Janigro is of great importance.

Read on for the excerpt from the booklet notes of this new APR release, in which I explain the backstory of these recordings, which are now issued on CD for the first time. As is usually the case with Lipatti, even more new information came to me in the last month since the production went to print – truly, this always happens with Lipatti! – but these new details will have to wait for the book that I’ll have to write on his recordings.

The excerpt below picks up after my discussion of the fact that Lipatti had agreed to record both a Beethoven Concerto (the pianist had requested to do so) and the Tchaikovsky Concerto (which Legge had requested) – despite the producer having famously stated that Lipatti had refused to record either, a lie that has been perpetuated ever since his oft-published 1951 Gramophone magazine tribute to the pianist (I have copies of signed memos written by Legge while Lipatti was alive that prove that his published statements are false).

So here, on to the recordings with Janigro:

Unreleased treasures

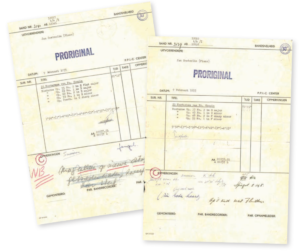

What might be even more surprising than these revelations is the fact that a set of records that Lipatti actually did produce was never issued by Legge either during the pianist’s lifetime or afterwards. Lipatti was touring Switzerland with cellist Antonio Janigro in May 1947, playing recital programs of sonatas by Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms to great critical acclaim. On 24 May they went to the Wolfbach Studio in Zürich to record six 78-rpm discs, among them the first movement of the Beethoven A major Sonata, Op 69. The session sheets for these records – matrix numbers CZX 221 through 226 – have at the top of each page the words ‘Test for Mr. W. Legge’.

It is surprising that the producer did not, at the very least, issue these discs posthumously, given the pianist’s great fame and the dearth of available recordings. One possible reason for his not having done so comes from a testimonial by Steven Isserlis, who studied with Janigro in the mid-1970s. The master cellist was speaking mournfully to his student about the lost opportunity of making records with Lipatti and when asked why they had not, Janigro said with the utmost bitterness in his voice, ‘because Mister Walter Legge didn’t like the cello’.

No correspondence by Legge or Lipatti discussing these recordings has been found so it is not known for certain how the session came to happen. However, a 1970 letter to EMI’s David Bicknell by Madeleine Lipatti states: ‘This was a private recording which was sent to Columbia by Lipatti’s wish, but this ‘test’ recording was not followed up.’ She added that she and the cellist wished to issue the recordings as part of a charity project for the 20th anniversary of Lipatti’s death that year and asked if ‘the matrix is still in Columbia’s archive’, but no reply was on file and her project never came to fruition.

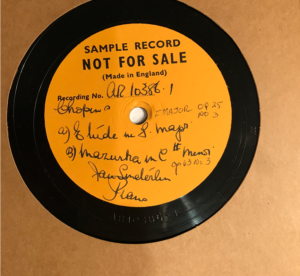

I became aware of the existence of these recordings in 1989 when Keith Hardwick of EMI responded to my inquiry about unpublished Lipatti recordings: he informed me that these discs had been borrowed from, but not returned to, the collection of the producer’s widow, Elisabeth Schwarzkopf. Investigations at EMI’s archive revealed that the masters no longer existed, but a few years later, pressings of two of the six sides were found in Dr Marc Gertsch’s collection in Bern, Switzerland, records he had received when Madeleine Lipatti died in 1983. My colleague Werner Unger and I issued these on Unger’s label archiphon as part of a 2-CD set featuring unpublished Lipatti recordings largely culled from Gertsch’s collection.

I finally made contact with Janigro’s daughter in Milan in 2008 and she introduced me to the cellist’s pupil Ulrich Bracher in Germany: he had five of the six discs and had in fact put the recordings out on a private cassette devoted to Janigro which had somehow never made its way into the hands of Lipatti fans. He graciously shipped the original acetates to Unger, who transferred and issued them in a digital release in 2014 and who has made them available for this present set.

The current release is the first published CD of these recordings to be made, over 70 years after the studio sessions. Unfortunately, the Chopin Nocturne in C sharp minor (CZX 224) that the artists recorded has not been located: it wasn’t mentioned in Madeleine’s letter, so it is possible that the disc was never pressed. The artistry of both musicians here is stunning, these records revealing, in the words of Isserlis, “such wonderfully sensitive, imaginative playing, and such mastery. A truly magnificent duo!” These performances’ absence from the catalogue both during the pianist’s lifetime and afterwards is most regrettable, but fortunately they are now available – a significant addition to the pianist’s discography.

You can order the CD set here (click bold text)

And here is that remarkable first movement of the Beethoven Sonata – glorious playing on the part of both musicians!

Recent Comments