It is truly astounding how some of the most amazing pianists are not as well remembered as some of their colleagues. It is a fact that while many great artists had notable careers, others did not pursue aspirations to tour internationally or record extensively. And yet the names of some very popular performers can easily fade from public consciousness after they die, particularly if their recordings become harder to come by (if any were made at all).

Victor Schiøler, a remarkable pianist whose name I first encountered in the last few years thanks to the internet, was a Danish musician who studied with two of the greatest legends of the piano, had a noteworthy career, and made many recordings. However, it was Schiøler’s own pupil Victor Borge who became the ‘great Dane’ of the piano, known the world over for his brilliant musical comedy, although when playing seriously (which he did on rare occasions), Borge was capable of the most exquisite pianism – no doubt due at least in part to the training he received from Schiøler. The comedian’s fame would eclipse his great teacher’s position as Denmark’s pre-eminent pianist, although Schiøler was quite well-known and very respected internationally in his lifetime, and is still remembered in his native land.

He was born into a musical family on April 7, 1899. His mother Augusta Schiøler was a pianist and her son’s first teacher, and his father was composer and conductor Victor Bendix. After beginning his studies with his mother, the young Victor would train with two of the most revered pianists of the time, among the most admired pupils of the great Leschetizky: Ignaz Friedman and Artur Schnabel. Schiøler’s debut took place in 1914 (he was only 15 years old) and he began touring as a soloist in 1919 – he also worked domestically as a conductor, appearing on the podium for the first time in 1923 and being conductor and musical advisor at the Royal Opera in Copenhagen from 1930 to 1932.

Schiøler toured internationally to great acclaim—America in 1948-49, Africa in 1951, and Indochina and Hong Kong in 1952-53—but his career was not limited to music. In addition to concertizing and recording, he also received a degree in medicine and practiced psychiatry! He had long been interested in medicine but had delayed studying it in order to follow Schnabel’s advice that he give concerts in Germany. When he stopped playing in that country due to Hitler’s ascent to power in 1933, he began the formal study of medicine. He spent the last two years of the War in Sweden, and would not return to Germany until after the War.

By his own admission, Schiøler had ‘a tendency to have too many irons in the fire – irons of the most different kinds.’ In addition to his concert and recording career, obtaining his degree in medicine, and professional psychiatric practice, Schiøler worked in other arenas of the musical scene: he was chairman of a committee to help performing artists with matters of contracts, royalties, and copyright. In his later years, he had a TV program in Denmark called ‘From the World of the Piano,’ and chose to limit his concert activities: as he wanted to spend as much time as possible with his family, he travelled only if his wife and son could accompany him.

He died in 1967, not long before his 68th birthday, leaving behind a significant number of recordings spanning a four-decade period. His first disc dates back to 1924 for the Nordisk Polyphon label – Chopin’s Berceuse and Valse Op.64 No.2 – and in 1925 he made his first record for HMV in England. Over the years he also recorded for Columbia, Sonora, and TONO, with several discs recorded by HMV and many of his performances being issued internationally on Mercury and Capitol.

He died in 1967, not long before his 68th birthday, leaving behind a significant number of recordings spanning a four-decade period. His first disc dates back to 1924 for the Nordisk Polyphon label – Chopin’s Berceuse and Valse Op.64 No.2 – and in 1925 he made his first record for HMV in England. Over the years he also recorded for Columbia, Sonora, and TONO, with several discs recorded by HMV and many of his performances being issued internationally on Mercury and Capitol.

His 1945 recording of Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No.1 on the TONO label would for a time be the best-selling classical record in Denmark. It was apparently the first Danish recording of a piano concerto, but its popularity was largely due to the opening of the work being used in a Barbett razor blade commercial screened at all Danish cinemas around the time, leading the theme to be locally known as the ‘Barbett Concerto.’ (The first record of the 4-disc set sold about ten times as many copies as the entire set as a result of its use in the commercial.)

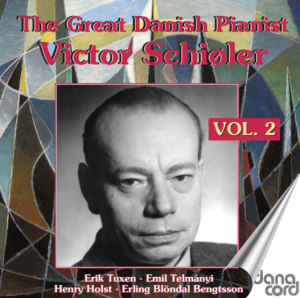

With several hours of recordings on a variety of international labels under his belt, Schiøler ought to be better known today, and yet with the exception of the release of two double-disc sets on the Danacord label from his home country, he has been largely ignored by the recording industry. All of his performances feature the qualities that are the signs of a truly great pianist: a rich vibrant sonority, a mindfully shaped singing line, attentive balance of harmonic support in lower registers (his chords are also beautifully voiced), rubato coordinated with musical architecture, and refined use of dynamic layering and pedalling. His recordings reveal style and individuality but never at the expense of the music – he seems to have always brought dignified discernment to his interpretations.

With several hours of recordings on a variety of international labels under his belt, Schiøler ought to be better known today, and yet with the exception of the release of two double-disc sets on the Danacord label from his home country, he has been largely ignored by the recording industry. All of his performances feature the qualities that are the signs of a truly great pianist: a rich vibrant sonority, a mindfully shaped singing line, attentive balance of harmonic support in lower registers (his chords are also beautifully voiced), rubato coordinated with musical architecture, and refined use of dynamic layering and pedalling. His recordings reveal style and individuality but never at the expense of the music – he seems to have always brought dignified discernment to his interpretations.

This 1929 recording of Schiøler playing two Scarlatti Sonatas arranged by Tausig – the once-popular Pastorale and Capriccio – captures the pianist’s beautifully burnished line in the treble register, precise and even articulation, judicious use of the pedal add an extra sheen to tonal colours, and marvellous sense of rhythm.

A fine example of Schiøler’s unerring good taste is this 1942 recording of Chopin’s famous A-Flat Major Polonaise Op.53, a work that is often delivered with bombast and self-centred virtuosity. In his reading, Schiøler does not shy away from power while emphasizing the nobility of conception and beauty of Chopin’s legendary work. What a full-bodied sonority, incisive rhythmic pulse, and transparent textures! Note how the bass sings through with great presence yet without obscuring the content of upper registers… superb!

Schiøler’s 1951 HMV recording of Liszt’s Piano Concerto No.1 (available on the first Danacord retrospective) features the same tasteful but thrilling playing, the Danish pianist’s sumptuous sonority, refined dynamic layers, and elegant phrasing all serving the musical content while still delivering excitement where the score calls for it.

Schiøler’s approach to the classical repertoire is no less mesmerizing, his glorious recording of Beethoven’s Sonata in C Minor Op.111 being a particularly fine example of his refined and noble artistry. His majestic phrasing, varied tonal palette, subtle nuancing, and magnificent voicing are a wonder to behold: particularly appealing is his manner of letting the bass sonority sing loudly without being brash or overpowering, without ever obscuring the melodic content (as is the case in the Chopin Polonaise featured above).

This film footage of Hansen from Danish television is a wonderful opportunity to see the pianist in action – and to hear him speak (all the better if you understand Danish). In this tribute to Schubert, the pianist first accompanies singer Ib Hansen in a reading of Der Wanderer before giving a brief lecture and launching into his own performance of Schubert’s Wanderer-Fantasie. Throughout, Schiøler demonstrates the same attention to tonal beauty, clarity of articulation, poised voicing, and fluidity of phrasing that characterizes all of his recorded performances.

The latest double-disc set from Danacord includes the pianist’s glorious 1956 traversal of Schumann’s Carnaval, a magnificent reading that captures to perfection the composition’s varied moods, with his long singing line, poised voicing, rhythmic bite, and marvellously proportioned rubato.

While it is a shame that Schiøler is not as lionized as many of his contemporaries, we are fortunate that at least some of his recordings are available on CD and via YouTube, and one hopes that a complete reissue of this fine artist’s performances will one day be produced. He is most certainly an artist worth hearing again and again in his many hours of recordings, all demonstrating truly intelligent, insightful, inspired pianism.

Recent Comments