The celebrated British pianist Benjamin Grosvenor has released the second CD in his much-publicized contract with Decca. After last year’s critically lauded solo disc featuring compositions by Chopin, Liszt, and Ravel, his new release focuses on works for piano and orchestra, giving listeners at home an opportunity to hear Grosvenor performing with an instrumental ensemble, in this case the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic conducted by James Judd.

The choice of works and presentation of the disc as a whole is an unusual one: Saint-Säens’ Second Piano Concerto, Ravel’s G Major Concerto, and Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue, each followed by a solo ‘encore’ by the respective composers. The Ravel is an interesting bridge between the two works – he was French like Saint-Säens and his Concerto includes jazzy elements at times similar to Gershwin – but as an overall flow it is not the kind of programming that would necessarily encourage all-at-once listening, nor is a quieter solo composition after each larger concerted work ideal on the ear, with their different sound levels having one reaching for the volume control.

Personally, I’d have loved to hear the Saint-Säens with the Liszt Second that Grosvenor performed so magnificently at last year’s Proms, as well as with the Schumann Concerto (I’ve heard a stellar broadcast performance that was astonishingly mature). Whatever the reason for the repertoire choices, entitling the disc ‘Rhapsody in Blue’ when the Gershwin is the shortest concerted work featured seems a bit misguided, since all of the works here are equally worth hearing. However, when presented with what are profound and dazzling interpretations of great music, such objections and considerations are soon overlooked.

Grosvenor’s style, as I commented when reviewing his solo disc last year, blends an unusual degree of refinement and precision with old-school impulsiveness and ‘edge’. Regardless of the work he is performing, his sound is beautifully polished and refined, even at its loudest never becoming hard (the promotional videos filmed during sessions give the impression of brittleness, no doubt due to the mic’ing on the video cameras), and his phrasing is elegantly crafted, always with a sense of line and forward momentum.

The Saint-Säens is newer in Grosvenor’s repertoire – it seems hardly coincidental that the CD was released the same week that he performed the work at the Proms (surely a sign of Decca’s marketing machine at work). If this is a concerto that he hasn’t played as often as the Ravel (which he has performed since age 11), Grosvenor has clearly given his interpretation much thought and consideration – not that his playing seems to lack spontaneity or impetuousness. If midway through the first movement he opts for some stronger accents than I might have liked, the playing is never less than musical or effective. The first-movement cadenza is remarkable for its poetic phrasing, brought about in part by masterful pedalling and magnificent tone production. In the second movement, Grosvenor achieves great buoyancy while maintaining clear voicing and sparkling tone, while the finale features tremendous drive and the sense of risk-taking despite the phrasing never being uneven and tone never being harsh. Truly thrilling playing.

Ravel’s brilliant Concerto in G (1932) receives here one of its finest recorded interpretations. Grosvenor is the only pianist other than the legendary Michelangeli who I have heard create the uncanny effect of somehow enunciating the trills in the first movement such that one appears to hear notes between the semitones, like a zither or musical saw. He navigates through the first movement’s lyrical and virtuosic passages with a seamlessness that is stunning. The sense of flow in the second movement is impressive, with long lines and unobtrusive articulation, and the rapidly paced third movement poses no technical or musical challenge for Grosvenor as he brings the concerto to an exciting close.

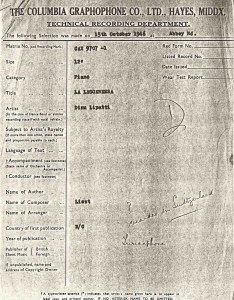

For the disc’s title work Rhapsody in Blue, Grosvenor and members of the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic – who provide admirable support throughout the disc but especially here – use the original 1924 orchestration by Gershwin’s colleague Ferde Grofé (which can be heard in the composer’s own abridged recording made the same year). The atmosphere in this more compact version is even more free-wheeling than usual, and here Grosvenor demonstrates that he is a master of whatever work he chooses to perform: an extraordinarily sensitive and refined an artist in ‘serious’ repertoire, he brings a jazzier, more popular work like this to life without lowering his musical or pianistic standards. Grosvenor unaffectedly fuses the work’s unique combination of jazzy and classical elements, with infectious vitality in his rhythmic drive, incredibly suave sensuality in lyrical passages, and crisply articulated passages flawlessly contrasted with fluidly phrased melodic lines. The measures leading into the famous secondary theme near the 9:30-mark may be the silkiest, most beguiling on record, and the subsequent rapid-fire repeated notes are technically brilliant while retaining purity of tone. This performance without a doubt ranks among the all-time greats.

The solo ‘encores’ presented between the major works are no less impressive. Godowsky’s arrangement of Saint-Säens’ The Swan is a perfect showpiece for Grosvenor, whose transcendent technique and Romantic sensibility enable him to bring out the transcription’s full potential: a primary melodic line that soars above the accompanying tracery, melting harmonies beautifully layered yet audible, timing wonderfully pliant and expansive. Ravel’s rarely-played Prelude in A Minor receives an exquisite reading that finds the composer’s experimental harmonies beautifully highlighted through Grosvenor’s delicate phrasing. The final solo, Gershwin’s Love Walked In, is one this young pianist has played for years. The trills, the balance of harmonies, and the incredibly supple phrasing are a marvel and provide a gorgeous closing to Grosvenor’s latest offering.

In short, this disc features performances as glorious as one could hope for. There is no doubt that the CD will be showered with justly-deserved praise, and hopefully sales will encourage the decision makers at Decca to record Grosvenor even more frequently, as one disc a year isn’t nearly enough for an artist of this calibre.

Recent Comments